Vulnerable persons

1. Overview

To a certain extent it may be argued that every party who comes to court is vulnerable; that the very requirement to submit to the court process, over which you have little control, is daunting. However, this chapter is not intended to deal with the majority who are nervous about participating in court proceedings, but rather with those who have a particular vulnerability. There is potential overlap with other chapters in this bench book, which may also be relevant to vulnerable persons. Readers may wish to have regard, for example, to those dealing with children and young people, those dealing with physical and mental disabilities, and/or those dealing with unrepresented parties.

Current legislative framework for vulnerable witnesses in criminal matters

Closed court: section 271(1) and section 271HB- criminal

Ground rules hearings and commissions

Reviewing special measures

Closed court- civil

TribunalsDomestic abuse

What is domestic abuse?

Who is involved?

Effects of domestic abuse

Adjustments that may be required

Reluctant complainers and contempt

Complainers in domestic abuse cases and warrants to apprehend

Non-harassment orders at the end of a criminal caseComplainers and sexual assaults

Rape myths

Arrangements for vulnerable accused

2. Who does this chapter relate to?

Witnesses and parties may be “vulnerable” in a court or tribunal as a result of various factors, and reasonable adjustments may need to be made as a result. Vulnerability may be as a result of a person’s disability, as a result of a lack of understanding as to the process, or because of fear. These are just examples.

The judiciary should be alert to vulnerability, even if not previously flagged up. Indicators may arise, for example, from someone’s demeanour and language; age; the circumstances of the alleged offence; a child being “looked after” by the local authority; because of the nature of allegations to be tested; or because a witness comes from a group with moral or religious proscriptions on speaking about certain matters.

There is a distinction between “reasonable adjustments“ which require to be made to comply with the Equality Act, and common sense changes that may be made by a judge to promote effective participation in the court or tribunal room. The England and Wales Bench Book, at appendix B, page 244 onwards, has a list of examples of reasonable adjustments that might be considered in the former case. These are in terms of the duty under the Equality Act 2010 but may assist with wider thinking about the issue beyond where a participant has a protected characteristic.

“Reasonable adjustments“ that may be required are many and varied. They will need to be considered where a vulnerable person has a protected characteristic and may also be usefully considered to assist any vulnerable participant.

Vulnerable witnesses in criminal proceedings are those described in section 271 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995.[1] In civil proceedings, the definition is contained in section 11 of the Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004.[2]

3. Expedited time scales

One of the repeated themes, in both civil and criminal courts and in tribunals, is the need to do everything possible to expedite time scales in cases involving vulnerable participants. Trial and case management powers should be exercised to the full where a vulnerable witness or accused is involved. A trial, proof or hearing date involving a young or vulnerable adult witness should only be changed in exceptional circumstances. It is thought that some vulnerable witnesses, for example children, will have reduced capacity to remember events if there is a delay, but in addition, delay is likely to exacerbate the stress of waiting for a trial or proof date. Complainers speak of their life being “on hold“ during the period between the alleged event and the trial, and it may well be the same for other participants.

4. The rights of the vulnerable to effective participation

Accommodating a vulnerable person’s needs (as required by case law, the Equality Act 2010, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities) requires the court or tribunal to adopt a flexible approach in order to deal with cases justly.

Vulnerable people are thought to experience much higher levels of communication difficulty in the justice system than was previously recognised. A Law Society of Scotland report published in 2019 noted:

“Age, mental health, learning difficulties, communication problems and physical impairment are all readily identifiable terms that may trigger and allow an assessment of vulnerability to follow. These factors reflect the ‘protected characteristics’ as defined in the Equality Act 2010. These could provide a starting point for considering vulnerability, but the roundtable discussion highlighted that this alone may not fully address the issue. Attendees at the roundtable confirmed that there are no clear guidelines on what account and relevance should be placed on alcohol or substance abuse, fear, minority interests, Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), distress and homelessness in establishing vulnerability.“

Individuals may have an inability to understand or communicate in court but may also be keen to hide this in order to maintain bravado. When judges are checking understanding, it is not useful to do so by asking the question: “Do you understand?“ This is likely to elicit a positive answer that may be false. Instead, an individual should be asked to explain what they have understood in their own words, and then be given the time and support to do so.

Historically, courts had common law powers to protect any vulnerable witness who would be disadvantaged by having to give evidence without adjustments (see Hampson v HMA 2003 SCCR 13).[3] These powers remain in as much as all courts and tribunals have a general duty to ensure a fair hearing, which will include making adjustments where necessary to assist a party or witness to give evidence and thus have a fair hearing.

5. Special measures

The first statutory powers specifically relating to vulnerable witnesses were contained in the Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004, which dealt with both civil and criminal cases, and which has been considerably amended and expanded upon subsequently.

In general terms special measures are:[4]

The use of a live TV link;

The use of screens;

The use of a supporter;

Taking of evidence by commissioner;

Giving evidence in chief in the form of a prior statement;

Excluding the public during the taking of the evidence;

Such other measures as may be prescribed by the Scottish Ministers in regulations; and

The use of pre-recorded evidence instead of testifying in court for child and other vulnerable witnesses[5]

6. Current legislative framework for vulnerable witnesses in criminal matters

Measures for child and vulnerable witnesses is an evolving area, with the Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill currently progressing through Parliament and due to make more innovations in this field, for example by creating a Victims and Witnesses Commissioner for Scotland;[6] and by increasing the availability of special measures in civil proceedings.

In addition, there is an ongoing roll out of provisions in the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019, which introduced the right for children and vulnerable witnesses in the most serious criminal cases to have their evidence pre-recorded. The implementation plan can be found here.[7]

Currently, section 271A of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 sets out the procedure to be followed by any party citing or intending to cite a child witness or deemed vulnerable witness. In usual circumstances, these notices should have been dealt with at or in advance of the preliminary hearing or first diet in solemn proceedings, having been lodged 14 or 7 days before the diet and 14 days before a summary trial (section 271(13A)).

A person is deemed to be a vulnerable witness entitled to special measures (section 271(5) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995) if they are the complainer in a sexual, trafficking, domestic abuse or stalking case.

Other vulnerable witnesses are defined in section 271(1). Broadly speaking, a person is vulnerable if there is a significant risk of the quality of their evidence being diminished by reason of mental disorder, or fear or distress in connection with giving evidence at trial. There is also a “catch all“ provision contained in section 271(1)(d) “where there is considered to be a significant risk of harm to the person by reason only of the fact that the person is giving or is to give evidence in the proceedings”.[8]

Closed court: section 271(1) and section 271HB- criminal

Section 271H(1)(ea) of the 1995 Act allows an additional special measure of having a closed court (ie excluding the public during the taking of evidence from the vulnerable witness). Section 271HB details how this special measure is to operate. It provides that:

members or officers of the court;

parties to the court;

counsel or solicitors or other persons otherwise directly concerned in the case;

bona fide representatives of news gathering or reporting organisations; and

such other persons as the court may specially authorise to be present

should not be excluded from the court.

This special measure does not apply where the vulnerable witness is the accused (section 271F(8)).

Section 92(3) of the 1995 Act: “From the commencement of the leading of evidence in a trial for rape or the like the judge may, if he thinks fit, cause all persons other than the accused and counsel and solicitors to be removed from the courtroom.“ It will be observed that this section excludes a greater class of persons than those mentioned in section 271HB.

Ground rules hearings and commissions

Reference is made to chapter 8 of the Preliminary Hearings Bench Book, which deals with vulnerable witnesses and evidence on commission.

The Advocate’s Gateway gives useful guidance on identifying vulnerability in witnesses (Toolkit 10), and on the questioning of witnesses with different types of vulnerability.

Reviewing special measures

Section 271D enables the court to change special measures at any stage of the proceedings, by ordering them, varying those already ordered or revoking them.

Closed court- civil

Some civil proceedings take place in private in terms of the applicable rules, for example adoptions or Child Welfare Hearings. Otherwise, the starting point is open justice. It may be a breach of Article 10 rights and breach the longstanding commitment to open justice to close a court. It could also be subject to challenge based on the perceived lack of any mechanism for challenge before the making of such an order, to close the court. Judges should be aware that the media can have a legitimate interest not just in watching proceedings, but also in access to certain court documents.[9] SCTS staff have access to a media guide to assist them.[10]

Nevertheless, it is easy to conceive of circumstances where it may well be appropriate to close the court for short periods or particular points in a case; for example, in a divorce action where one of the parties alleges rape. That may mean the public (but not media representatives) are excluded for a period.

Meanwhile, reference is made to the ability to make reporting restrictions and the strict procedure for doing so. Particular reference is made to the need for a written motion and Form 48.1A in terms of Rule 48.1A of the Ordinary Cause Rules, as amended. There are similar Court of Session rules and Sheriff Appeal Court rules – see chapter on children and young people.

Tribunals

Much of what has been said in relation to court applies to tribunals.

Tribunal rules are likely to have been drawn up to allow tribunal judges to protect vulnerable persons and these require to be followed. The Upper Tribunal (in a benefits tribunal case, but one which has universal application) has held that children and vulnerable witnesses and parties have a right to special considerations when appearing before a tribunal and failure to have regard to these may constitute an error in law.[11]

In employment tribunals in England and Wales, there is Presidential Guidance in relation to vulnerable parties and witnesses (including children). The Immigration and Asylum Chamber have similar. The Guidance suggests “vulnerability” could be defined as where someone is likely to suffer fear or distress in giving evidence because of their own circumstances or those relating to the case. The Guidance states that the tribunal and parties need to identify any party or witness who is a vulnerable person at the earliest possible stage of proceedings. They should also consider whether the quality of the evidence given by a party or witness is likely to be diminished by reason of vulnerability.[12]

7. Taking evidence, including from vulnerable persons

Vulnerabilities can arise due a multitude of factors: physical disability, mental health, learning disability, low educational attainment, or poverty. Vulnerability can also arise from the nature of the allegations a witness is to speak to. This is particularly the case where there are allegations of sexual or domestic abuse (both in a civil and criminal context). There is, therefore, a crossover with the sections on domestic violence in the sex chapter and sexual violence in the same chapter.

Judges may find it useful to consider the terms of section 271 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Even in a civil case, this might assist with providing a framework of factors, alerting a judge to a vulnerability or diminished quality of evidence. (The quality of evidence is defined in this section as the completeness, coherence, and accuracy of the evidence). The 1995 Act sets out factors such as being under 18, having a mental disorder, fear, or distress as to giving evidence, being a complainer in a matter of alleged sexual offending, trafficking, domestic abuse, stalking. Other factors to be considered include the nature and circumstances of the alleged offence, the nature of the evidence the witness is likely to give, the relationship between the accused and the witness, the witness’ age and maturity, any behaviour towards the witness by the accused or by their family members or associates. Factors particular to the witness should also be considered, including the social, cultural, and ethnic origins of the witness, their sexual orientation, their domestic and employment circumstances, their religious beliefs and political opinions and any physical disability or impairments.

If a judge considers a witness is vulnerable, there may be formal steps that the judge should take depending on the setting, and whether in a tribunal or in a court. These may require the judge to make formal orders for measure for that witness’ evidence, or to raise the issue with the parties. A judge will need to be alert to the necessity to review and revise the approach taken during the witness’ evidence if it appears that the witness’ evidence may be diminished due to their vulnerabilities.

In a criminal setting, judges are reminded about the line of cases setting out the need to control cross-examination, particularly in cases of sexual allegations (see for example Begg or Dreghorn v HMA 2015 SLT 602, Donegan v HMA 2019 JC 91 and MacDonald v HMA 2020 JC 244. Whilst such cases have arisen in trials concerning sexual allegations, they are definitive guidance on the standards of cross-examination and set out the clear obligation on the judge to control questioning. Attention is drawn to the court’s words in paragraph 33 of MacDonald v HMA.[13] See also Docherty v PF Greenock [2012] HCJAC 155 at paragraph 6 (arising in a summary trial concerning a non-sexual assault), McLintock v PF Edinburgh [2013] HCJAC 6 at paragraph 7 and KP v HMA [2017] HCJAC 57 at paragraph 19. It is clear such rules apply equally to all witnesses across a range of issues (and forums) and, in criminal matters, also to when the accused is giving evidence.

As such, judges should be alert as to whether the accused has particular vulnerabilities if giving evidence. In civil cases, vulnerable persons may include the parties themselves. As judges are not always told in advance of vulnerabilities, it may be necessary to slow or stop proceedings and make enquiries.

Matters to consider for all witnesses but particularly to be alert for in vulnerable witnesses:

Cross-examination should test a witness’ evidence, but should be “properly directed and focused“ (Begg or Dreghorn v HMA at paragraph 38). Irrelevant questions should be stopped (MacDonald v HMA at paragraph 47).

The tone of questioning. Whilst difficult questions may need to be asked of witnesses, questioning should not be in a tone that suggests incredulity at an answer, or in a belligerent or hostile tone. Judges may need to remind agents/counsel that it is for the court/tribunal/jury to be the decision-maker, not the agent. In the same vein, judges should remember that their comments in courts are public (Donegan v HMA at paragraph 55).

Cross-examination should not be insulting or intimidating to a witness (Begg or Dreghorn v HMA at paragraph 38). Judges can stop questioning that is “protracted, vexatious and unfeeling“ (Inch v Inch at page 998, quoted with approval in Begg or Dreghorn v HMA at paragraph 40).

Judges should ensure any of their own questions, to clarify a matter or where a judge requires to intervene for a legitimate purpose, are appropriate in tone and content (Donegan v HMA at paragraph 54).

The speed of questioning. Judges should be alert to the witness failing to keep up with questions. Questions should not be “fired” at witnesses. Many people require time to think before answering. Taking a moment or two to respond can reflect an individual’s need for thinking time due to working memory or processing speed. It might also reflect that the questioning is on a difficult issue, rather than a credibility issue.

A witness becoming confused if questions jump between topics. A less experienced agent may need gentle guidance to encourage a logical approach of chapters of evidence.

Repeated questions. If questions are repeated, this suggests questioning is not properly directed or focussed (see above) and also raises an issue as to the length of cross-examination (see below). If there is a genuine misunderstanding over a witness’ answer that justifies repeating a question or line of questions, judges may wish to intervene to clarify. A witness, particularly if struggling to articulate themselves, is likely to become frustrated at the same question being asked multiple times. They may not have the range of vocabulary to answer the question in a different way and become irritated at repeating the same answer.

In the same vein, the length of questioning. Cross-examination should be focused. A judge can set down a time limit for questioning (Begg or Dreghorn v HMA at paragraph 40).

A witness misunderstanding the question. The language used in many judicial settings is often alien to most people’s lives. Likewise, language used by witnesses can be different to what many professionals use in their day to day lives. Judges should be alert to a witness who appears “at times to struggle to decipher the meaning of questions;”[14]

Sometimes agents/counsel can misunderstand what a witness has said (or what a witness might be trying to say but struggling to articulate). Often this leads to a line of questioning which may further confuse the witness. Again, judges should intervene when necessary.

If it is necessary to ask a witness to leave the courtroom to deal with an objection, it is helpful to offer a few words of explanation to settle the witness; many witnesses think it is their fault that they are being asked to leave having said something “wrong”;[15]

Offer breaks when needed. Be wary of the witness who wishes to press on despite being clearly upset. It may be more useful for the judge to impose breaks in those circumstances even of just a few minutes at a time (and perhaps remaining on the bench/in the tribunal room depending on the circumstances). Alternatively, allowing a witness time to compose themselves might be sufficient, with the reassurance that a break can be taken if needed.

The timing of a witness’ evidence. Children and young persons should not generally be asked to give evidence late in the day, particularly outwith school hours. Separately, starting a vulnerable witness’ evidence late on a Friday afternoon has been noted to cause issues for them;[16]

Be aware of terms that might be used by young witnesses and children to describe their bodies: judges might find the Relationships, Sexual Health and Parenthood resource helpful. Whilst some topics within it have been criticised, it provides resources for schools in teaching the terms “penis, vulva, nipples and bottom“ to children in early years of primary school.

Judges must ensure that, whilst attending court may still be nerve-wracking, emotionally draining and might involve recounting a traumatic experience, the individual is treated in court with dignity and respect. A witness, whether the accused, a party, or a complainer, should always be put in the position of being able to give their best evidence to the court.[17]

Trauma

It is essential that judges understand the impact of trauma on witnesses and accused persons and, importantly, understand the steps that judges should take to avoid witnesses and others to become more traumatised after court proceedings. The current draft of the Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill is likely to introduce some statutory provisions on trauma informed practice.[18] All judges should be familiar with the concepts of trauma set out in the Trauma Informed Judging Resource Kit. There is increasing scrutiny as to whether courts respect not only the rights of accused persons, but also witnesses. If judges fail to do so, it might result not only in a failure of justice in an individual case, but also a wider risk of the public failing to have confidence in the court system. In addition, and whilst there are crossovers between trauma and domestic abuse or allegations of sexual assaults, the issue of trauma goes beyond those subject matters. Many civil cases involve traumatic events or vulnerable witnesses, such as personal injury, adoption or matters before tribunals.

It is important to give the witness as much predictability as possible around giving evidence. Simple information about the process should be provided. Psychologists advise that where a court provides a witness with choice or control over the situation, this can improve the witness’ experience. Accordingly, a court should do so if the option exists. This recognises the lack of safety and control inherent in the traumatic events to be spoken to in evidence. Where the court or tribunal provides predictability and choice, this can help minimise the extent to which the feelings of lack of safety and control are prompted by the experience of giving evidence. For example, if a witness has been told that their evidence will start at a particular time, this should be adhered to.

Reference is made to the list in the section on taking evidence from vulnerable witnesses but also:

Make eye contact with the witness on their entering the witness box/commission room, but bear in mind that in some cultures, eye contact is not routinely made.

Use plain language, and a calm and welcoming tone.

Discourage all in court from using legal jargon (which the toolkit notes can cause not just confusion but also disempowerment).

If needed, provide reassurance or an explanation about the way special measures operate.

Describe the likely progress of the court day, giving the witness the choice of sitting or standing, and checking the witnesses understand that breaks can be provided.

If evidence is to be lengthy, a scheduling of breaks throughout the day can help increase predictability.

If there is an interruption, giving the witness an appropriately expressed explanation is a simple courtesy and reassurance.

Ensure that questioning is straightforward, sequential and structured, making it easier for a witness to provide a coherent narrative.

It may be appropriate to explain a rule of evidence which is restricting the way the witness can answer questions and, if necessary and appropriate, to translate unfamiliar legal language.

Challenge agents or counsel who ask compound questions with more than one proposition.

Ensure that witnesses are not insulted, belittled, or intimidated. this, already, is an inherent judicial function, see Dreghorn v HM Advocate [2015] SCCR 349 and the other points raised in the section on taking evidence from vulnerable persons above.

Witnesses should not be rushed, should be given time to think and questions should not be expressed with a tone of suspicion or disbelief.

Intervene when necessary to ensure that questioning is fair and appropriate, giving a witness confidence that their interests are respected and will be protected.

8. Domestic abuse

What is domestic abuse?

Judicial office holders will be aware of the increased knowledge and research surrounding different types of domestic abuse, which has most recently involved the bringing into force of the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018. This expanded previous domestic abuse offences to include controlling behaviour, isolating behaviour and restricting behaviour, along with other types of behaviour. Traditionally “domestic abuse“ had a narrower ambit, more directed towards physical assaults and verbally abusive behaviour, and this expansion reflects society’s increased knowledge and understanding of the profound effects of inter-partner and inter-family abuse. Research findings published in 2023 about the 2018 Act make interesting reading.[19]

The findings show that complainers continue to feel that the most difficult thing to explain is psychological abuse. They also show the fact that many complainers themselves do not understand all the effects of abuse upon them or how the court process works; and consequently, they feel very vulnerable within it.

Separately, research suggests a lack of confidence from complainers in courts’ sentencing on domestic abuse. Issues raised include whether remorse should be taken into account in sentencing, with some participants questioning if judges have sufficient understanding of domestic abuse. There were also critical comments made as to what was perceived to be an inconsistent use of non-harassment orders.[20]

There are also issues of intersectionality with domestic abuse.[21] The term “intersectionality“ is used to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics may intersect and overlap with each other, increasing discrimination and/or oppression.[22]

Who is involved?

Domestic abuse can be perpetrated by anyone involved in a relationship, be they male or female. Such abuse can take place in all types of relationships, either in mixed or same sex relationships. Such abuse can also be against children in a family. However, most complainers in domestic violence and abuse cases are female.

In 2020-21, the clear majority (82%) of incidents of domestic abuse involved male accused (where it was known whether they were female or male). Of these, 80% involved a female complainer.[23] Smaller proportions of incidents involve female accused. In 2020-21, 16% of domestic abuse incidents involved a female accused and a male complainer, and 2% involved a female accused and a female complainer.

Judges will be aware of the need to treat complainers in criminal cases sensitively. There is an increasing understanding of the difficulties for complainers giving evidence, even with special measures such as screens or giving evidence remotely.[24]

Complainers report the process as emotionally draining and are often concerned as to the adversarial nature of criminal cases.

Judges should also be live to the occasional need to intimate to, and hear from, a complainer. In PF Falkirk v BM [2023] SAC Crim 12, where the accused sought to recover the complainer’s telephone records, the Sheriff Appeal Court held that the application engaged the complainer’s Article 8 rights and should have been intimated to her. She should also have been informed of her right to be heard and the possibility of obtaining legal aid, and an execution of service should have been lodged with the court. Various observations about the necessary specification in such an application and other procedures to be followed are also included. In civil cases, the question of at what stage intimation should be made to an individual whose Article 8 rights are affected by the recovery of sensitive records was considered in East Renfrewshire Council v Wright [2024] CSOH 70.

In respect of jury cases, judges are reminded:

There is a standard direction to be given as part of the written directions at the beginning of the case on domestic abuse, found in Part C of the written directions; and

Direction 3 in the Jury Manual, on delayed reporting, arises from the statutory framework for sexual assault cases, but, as the Jury Manual notes, it may have a relevance to domestic abuse allegations under common law.

Effects of domestic abuse

The effects of such abuse can be wide-ranging and long-standing. They can include a change in a victim’s personality or normal demeanour, at worst leading to suicidal ideation and major psychological effects. It may be thought that a victim in such circumstances can or should just leave the relationship. There are many reasons why this can be more difficult than may at first appear.

Danger and fear can be a major factor. 41% of women killed by a partner or former partner in England, Wales and Northern Ireland had left or taken steps to leave. 81% of these were killed in their own home (or one shared with the perpetrator).[25]

Isolation can be another main reason: abusive men often sever or weaken the woman’s connections with friends and family, so they have nowhere to turn for help. Trauma and low confidence, shame, embarrassment, and denial along with practical reasons, may also have a role to play.

It will be appreciated that all of these effects are likely to leave complainers in such cases in a fearful and vulnerable state, requiring patience and understanding in the court or tribunal setting.

Adjustments that may Be required

One crucial thing to ensure is that the alleged perpetrator of domestic abuse and the complainer do not come into contact with each other in advance of or during proceedings, unless or until any necessary provisions for this situation have been considered by the court or tribunal.

In criminal cases, a complainer will be entitled to special measures (see above) and this should have been contemplated and resolved in advance of any trial. In addition, members of court staff should have tried and tested procedures for ensuring that Crown witnesses and vulnerable witnesses do not come into contact with accused persons.

However, in civil cases the position may be more difficult. Any such issues should be explored as early as possible in the case, particularly given the requirement for parties to now personally attend an Initial Case Management Hearing in all family cases. Section 8 of the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 gives the court additional powers to order the use of special measures for vulnerable parties. This section is not yet in force, but it is anticipated it may come into force during 2025. Importantly, such an order can be made whether or not it has been applied for by a party. In short, where the party would be classed as a vulnerable witness, the court must order special measures. And where the party may be distressed by attending or participating in hearings, and this would be reduced by the use of a special measure, and such a measure wouldn’t give rise to a significant risk of prejudice in the case, then the court may order the use of such a measure.

Although this provision relates to family actions, care should be taken in all types of civil proceedings, whatever the subject matter or type of hearing. Not all agents will give the court advance notice of bail conditions or of the possible impact on a party if they were to encounter an alleged abuser. Judges need to be alert to the issue and carefully consider how best to manage it. Child welfare hearings can pose particular difficulties. Judges may need to think about staggered hearings with only one party in the court room at a time or the use of screens. Whilst virtual hearings may initially appear attractive to get round some difficulties of having both parties physically present at a child welfare hearing, such hearings may raise other issues.[26] Section 4 of the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 is not yet in force at the time of writing. When it comes into force it will authortise the court to prohibit the parties conducting their own case in children’s hearing referrals, or residence/contact proceedings; with the attendant requirement to appoint a solicitor from a register established under the Act to represent the party. The position, in the meantime, is considered further in the chapter on unrepresented parties.

Judges dealing with family cases should be aware of recent academic research raising the issue as to whether the importance of domestic abuse allegations is sufficiently understood in family cases,[27] and criticism of judicial handling of such cases.[28] Judges may wish to consider if the issues around allegations of domestic abuse are sufficiently focussed at an initial child welfare hearing, making such orders as required to address any lack of specification eg ordering previous convictions to be produced, copies of pending complaints or indictments, or adjustment or amendment of the pleadings so matters are properly pled.[29]

Further information available on the Judicial Hub includes two toolkits:

Domestic Abuse Resource Kit, including a useful e-book on vulnerable witnesses; and

Other resources that may be useful for judges include:

Briefing Paper: Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004 (now of some vintage).

Briefing Paper: Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019.

Contempt of Court Toolkit (but judges are asked to note that as it has not been updated for some time caution should be exercised) but reference should also be made to the section on vulnerable persons.

The issue of compensation orders in criminal cases is considered in Briefing Paper: The Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014.

See also the sections on taking evidence from vulnerable witnesses and trauma.

Reluctant complainers and contempt

Most judges will be familiar with complainers in domestic abuse cases who called the police at the time of an alleged offence, but who do not wish to give evidence about it in court. This may present as an alleged inability to remember what happened, as a proclaimed desire not to be at court or as a substantial diminishment of what allegedly occurred in their evidence.

There can be complicated reasons for such a position. The witness may be fearful, they may have already reconciled with the accused, they may feel embarrassed or under extreme pressure. Often such feelings won’t be assisted by the court also bringing pressure to bear, for example, by threats to find the witness in contempt of court. It should not be assumed that a witness is wishing to be defiant or obstructive and judges should consider carefully before embarking down the route that may be entirely appropriate for a recalcitrant witness in a different type of case. It might be thought that the test for contempt, that is whether the person is in wilful defiance, is a high test.[30]

Complainers in domestic abuse cases and warrants to apprehend

It is understood that COPFS policy is that warrants to apprehend complainers in domestic cases will only be sought in exceptional circumstances.[31]

If any such motion is made judges are recommended to consider what information may be available on the vulnerability of the complainer and to consider the impact on any children in the household.

Non-harassment orders at the end of a criminal case

Judges are reminded of the need to consider the imposition of a non-harassment order at the end of any case where domestic abuse is found to have taken place. The terms of the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 bring with them a presumption that such an order will be made, with an explanation required (and to be recorded in the court minute) in any case where an order is not made. Importantly, the order may also require to cover children. A Judicial Institute Briefing Paper covers this in detail.

9. Complainers and sexual assaults

Like domestic abuse, it is thought there is under-reporting of sexual assaults.[32]

Whilst it is always part of a judge’s function to ensure that all participants in court proceedings are treated fairly and sensitively, this has particular resonance where there are allegations of a sexual assault. Most complainers report being unprepared for giving evidence.[33] Whilst some complainers speak of the trial process bringing a sense of closure, others say the process involved further trauma to the extent that complainers report being treated in an “inhuman” way.[34] See also the sections on taking evidence from vulnerable witnesses and trauma.

Judges will be aware of the obligation on the court in terms of section 274 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) 1995 Act, designed to protect complainers in sexual offence trials from inappropriate questioning about their sexual history and character. There is a useful toolkit – Applications under s275 of the CPSA 1995 – on the Judicial Hub, together with guidance in chapter 9 of the Preliminary Hearings Bench Book. These give a framework to help consider any section 275 application.

Although the complainer must be told of the content of the section 275 application and be invited to comment or make objections to it before it is granted,[35] research suggests this is not being universally done.[36]

Points to note on sections 274/275 in practice:

Ensure that the Crown can relay the complainer’s views on the application, bearing in mind that simply because a complainer accepts the factual premise of the application does not mean it is relevant at common law or otherwise should be granted.

Remember the terms of section 274 – that “the court shall not admit or allow questioning….“ (emphasis added). Whilst the Crown may object, it is the court’s responsibility to control questions that fall foul of section 274, whether or not the Crown object.

Careful preparation is essential to enable a judge to appropriately intervene and be alert to the live issues in the case.[37] It is necessary to be familiar with the papers in advance, including the indictment, or complaint, any special defence, the minutes, any section 275 application and the decision on it, the vulnerable witness application, written questions if ordered, the joint minute, any prior statements, any police interview with the accused, and productions for both sides.

In the sheriff court, where commissions are rarer, practitioners may not be so familiar with the obligations of section 274. It can be useful to remind both the Crown and the defence of its terms at an early stage.

Again, particularly in the sheriff court, many practitioners may not be so familiar with the culture arising from a trauma-informed practice. It may be useful to raise this at an early stage. It can be useful to direct practitioners to the High Court practice notes on vulnerable witnesses and, if appropriate, to direct written questions that are made available in advance.

Similarly in relation to applications for recovery of medical, phone or other records relating to the complainer, guidance is available in the section of common law applications for disclosure in chapter 3 of the Preliminary Hearings Bench Book. In civil cases, the stage when intimation should be made to an individual whose Article 8 rights are affected by the recovery of sensitive records, was considered in East Renfrewshire Council v Wright [2024] CSOH 70.

Rape myths

In 2023, the Jury Manual was amended to include material for juries on rape myths. The general written direction is to be given at the start of the trial and may have to be amended to cover the specific charges before the jury. Direction 2 deals with consent, direction 3 with delay in reporting, direction 4 with the absence of physical resistance and force, direction 5 with prior inconsistent statements and direction 6 with a background of domestic abuse (also a written direction given at the start of the trial) and direction 7 with a complainer’s reaction to being questioned. As is noted in the Jury Manual, and by Lady Dorrian’s Review Group on “Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases”, there is much to be said for giving the relevant directions both in the introductory remarks at the start of the trial or otherwise as soon as the point arises. If giving rape myths directions during evidence, it may be wise to remind the jury that these will be matters to be considered by them when they come to consider their verdict and after having heard all the evidence, speeches and the judge’s further directions.

The background is that research from 2019 from mock jury deliberations found evidence of false assumptions, including as to how a rape victim “should” react, and that lack of physical resistance is indicative of consent.[38] Following this research, one of the researchers concluded that, “there is overwhelming evidence that rape myths affect the way in which jurors evaluate evidence in rape myth cases…”.[39]

In addition, Lady Dorrian’s Review Group recommended that steps should be taken to improve jury involvement in sexual offences cases, including a pilot programme to communicate information to juries on rape myths and stereotypes, together with the current statutory directions to address rape and sexual assault stereotypes.

Judges should:

Ensure the jury directions on rape and sexual offences are appropriately used, including the written directions at the commencement of the trial together with (as required) those for charging the jury.

The Judicial Hub has a number of resources available on sexual offences, including:

Taking Evidence by Commissioner (resource kit section of hub); and

Section in the Jury Manual on Addressing rape and sexual offence myths and stereotypes.

Some specific measures that judges may wish to consider include some words around explaining why a legal objection has arisen (arising from the fact that complainers appear to perceive that this is their “fault” for something they have said in their evidence). Other measures might include consideration of when a witness’ evidence is taken,[40] intervening early at inappropriate questions[41] or at behaviour of the accused in court (even if that behaviour might not be clear cut, but may be open to different interpretations, with particular care to take a neutral tone in such circumstances).

Recent research also suggests that it is important to complainers to have a clear understanding of the sentence imposed, and the reasons for it. The research also highlights the importance, for at least some complainers, of being able to attend the sentencing hearing, but also the difficulties this might entail given the issues of the lack of special measures, the travel that may be involved and that observing the hearing remotely is not a standard mechanism offered.[42]

Judges are reminded to consider non-harassment orders where there is a conviction in a sexual case.

Whilst the directions for rape myths arise in a criminal context for jurors, judges may also find it helpful to refer to them when facing such factual matters in a summary or a civil context. If a party is unrepresented in a civil case with allegations of sexual abuse, please refer to the section on this in the unrepresented parties chapter.

Arrangements for vulnerable accused

The statutory scheme for special measures for an accused is different from that for witnesses and is limited to the accused giving evidence.[43] Some statutory provisions explicitly exclude the accused (for example s271BZA regarding commissions). Section 271F sets out modifications to the provisions for vulnerable witnesses insofar as they apply to the accused giving evidence.

The absence of statutory provision for a vulnerable accused (outwith any evidence they may give) has been the subject of criticism.[44] Judges may wish to consider what other measures may be required, including breaks, the involvement of advocacy workers and intervening if it appears the accused is not following proceedings.[45] It is understood that in least one case, a sheriff has allowed an advocacy worker to sit with an accused in the dock, with the purpose of ensuring the accused is following the proceedings, and to highlight to the court if the accused is not. Such measures may allow an accused to participate in a trial.[46]

In England, there has been some use of intermediaries at stages in the justice process. An intermediary”s role ranges from carrying out a communication assessment, advising the court/tribunal/police accordingly, and, in some cases, advising on draft questions.[47]

See also the section on child accused.

10. Modern slavery

The latest figures available from the Home Office show that there were 387 potential victims of modern slavery in Scotland. [48] This may well be an understatement, with many victims not being discovered. This can involve trafficking people into the UK and then sexually exploiting them or forcing them into labour. The most common nationalities of those identified as victims in the UK in 2022 were Albanian (27%), UK (25%) and Eritrean (7%), followed by Sudanese and Vietnamese.[49] The most common form of exploitation is labour exploitation, with the construction industry, agriculture, the sex industry, nail bars, car washes and cannabis farms all featuring.[50] Trafficking is an offence under the Human Trafficking and Exploitation (Scotland) Act 2015. That Act also covers slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour. The offence is aggravated if committed against a child or if committed by a public official.

Section 8 of the Act places an obligation on the Lord Advocate to make and publish instructions on the prosecution of individuals who have been the victim of human trafficking or exploitation, in recognition of their particular vulnerabilities.

A National Referral Mechanism has been created to enable potential victims to be housed and supported while an assessment is made as to whether they are a victim of trafficking or slavery. It is understood that the mechanism is currently backlogged, and delays may occur as a result.

It is important to note that such victims are likely to be vulnerable witnesses, who may have been damaged by their experiences and may be anxious around displays of authority. Sensitivity and patience may be required when dealing with such individuals. It must be borne in mind that an underlying vulnerability, such as a learning difficulty or drug problem, may be the reason they have been prone to exploitation in the first place.

The Modern Slavery Act 2015 is mainly applicable in England and Wales, but some parts do apply in Scotland. In a 2016 review of the Act by barrister Caroline Haughey, the author recommended all victims of such offences should be treated as vulnerable, with the same Advocate’s Gateway questioning protocols that apply to victims of sexual offences being applied to them

11. Poverty

There are a number of different ways to measure or define poverty, including relative poverty,[51] absolute poverty,[52] and persistent poverty.[53]

Successive Scottish Governments have legislated by setting targets for the reduction of child poverty in Scotland by 2030 (see the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017), using four methods to measure progress. These are: the number of children in relative poverty, the numbers in absolute poverty, the numbers in persistent poverty and those in low income and material deprivation combined. Additionally, the Scottish Government also estimates levels of food insecurity,[54] a metric closely associated with poverty.

The latest data from the Scottish Government suggests that just under one quarter of children (24%), 21% of adults of working age and 15% of pensioners live in relative poverty in Scotland.[55] Many working age adults and children live in poverty although they are part of a household with an adult in paid work. The risk of poverty is uneven across population grounds with, for example, higher rates of poverty among single parent households.[56] Charities report that following COVID and the cost of living crisis, demands on services such as foodbanks have increased. Living in poverty is associated with lower life expectancy and poor health outcomes, lower educational attainment and risks of involvement in the criminal justice system.[57] A campaigning charity, the Child Poverty Action Group, has published “Poverty in Scotland 2021: Towards A 2030 Without Poverty” which describes trends and key issues.

Some common myths about poverty include that it is only families without an adult working that suffer poverty (often those in poverty are in work) or that those in poverty are lazy (many in poverty have a physical or mental disability impairing ability to work, or young children with difficulties over childcare). Rather, the underlying causes of poverty are complex, connected to matters such as the availability of types of work in the labour market, low level of skills and education, and social factors such as lone parenting and disability.[58]

There are links between low attendance or attainment at school and poverty in later life.[59] This is likely to be particularly acute post-COVID, given the levels of absenteeism in schools.[60]

There is a link between poverty and those involved with the criminal justice system, whether as an accused or as a witness,[61] although judges should be careful to note that for some crimes, such as domestic abuse, there does not appear to be a link with poverty levels. In 2021/22 Scottish Government statistics showed that 33% of people arriving at prison came from the 10% most deprived areas in the country.[62]

Judges should be careful not to stigmatise those in poverty. Often those in poverty will try to conceal it, particularly young people at school who may be aware of costs of school trips and other extras, such as non-uniform days. Sensitivity should be used, particularly in family cases.

12. Literacy and numeracy

An annual summary of attainment and school leaver destinations is published by the Scottish Government. A small number of pupils leave school with no qualifications (2.2%) but most (96%) leave with one or more passes at SCQF Level 4. It should be noted that SCQF Level 5 is broadly considered equivalent to what was previously known as Standard Grades or O-Grades, generally sat by pupils in S4 of secondary school. Table 8 of the summary shows stark differences in local authority areas, ranging from 3.8% of pupils in East Renfrewshire leaving school with a qualification lower than an SCQF Level 5, compared with 21.4% of pupils in East Lothian. In addition, the Scottish Government published data that estimates attainment in reading, writing, listening and talking, and literacy and numeracy by primaries 1, 4, 7 and in third year of secondary school.

Looking at the population as a whole, one report has estimated that just under 10% of the population in Scotland have low or no qualifications, defined as whether they have a qualification at SCQF level 4 or above.[63] Four local authority areas had higher percentages, that is to say more people with low attainment: West Dunbartonshire at 15.8%, Inverclyde and North Lanarkshire both at 14.6% and Glasgow City at 13.5%. At the other end of scale, around 1 in 3 adults have a degree level qualification in Scotland, but with stark local variations, ranging between 50% of adults in Edinburgh, but only 21.7% in West Dunbartonshire. The 2022 census captured some broad education statistics: just over 750,000 adults in Scotland responded to say they have no qualifications, from a response of 4,548,589 of adults over 16 years of age.

Academics have been critical of the data available. Professor Lindsay Paterson of Edinburgh University has argued that a SCQF level 4 qualification is not necessarily a qualification in numeracy or literacy. He points out that someone without a maths or English qualification at SCQF level 4 but with a qualification in, for example, woodwork at that level, would not be counted as having low or no qualifications but may still struggle with understanding.[64] With that in mind, it might be argued that little is known about the literacy and numeracy rates in Scotland.[65]

13. Communication

It is extremely likely that many cases in a court or tribunal will involve persons with additional communication needs. There are a disproportionate number of persons with a learning disability within the criminal justice system.[66] There is some evidence suggesting that those with a communication difficulty are more likely to reoffend.[67] It has been suggested that as many as 50% of prisoners have problems with language,[68] 40% of people in prison aged over 55 have a cognitive impairment which may impact on their communication[69] and as many as 20% of people attending court have a learning disability.[70]

It is thought that people with a communication difficulty are often skilled at hiding it,[71] leading to many communication issues being undiagnosed.

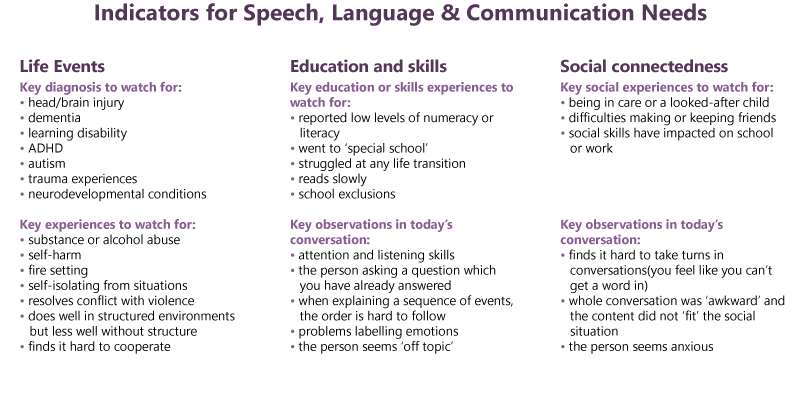

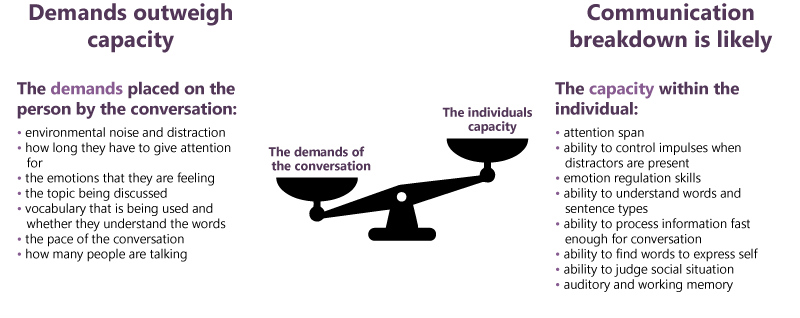

The following diagrams are a useful explanation of the type of indicators that may suggest a speech or language communication need (and are reproduced with the kind permission of Jacqui Learoyd).

Dr Susan McCool, a speech and language therapist, has produced a ten top tips checklist for best practice for working with those with speech and language difficulties.[72] It is provided below. As it is not a specific list for judges, not all the tips in it will be relevant. However, it might assist with a better understanding of the way professionals should overcome barriers for those with communication issues.

Technology is transforming the tools available to assist communication. “Talking mats”[73] is a visual communication framework which supports people with communication difficulties to express their feelings and views. It has been developed by speech and language therapists and may assist in reducing anxiety and supporting people to express how they really feel.

14. Remote witnesses/evidence by link

Judges will likely require to operate the in-court equipment for connecting with a vulnerable witness. Once used a few times, the operating of the equipment is relatively straightforward. Judges may wish to familiarise themselves with it before using it for the first time. It is important that the judge makes agents aware of the short delay whilst the camera swings to the correct position.

Eye contact with the remote witness is made by looking at the camera, not the monitor where the witness should appear. It may be appropriate to explain this to parties, to avoid any suggestion of discourtesy.

If there is an objection for which the witness should be excluded, good practice is to return the camera to the judge, explain there is a short legal matter to be dealt with and that the camera will be switched off for a short period. It is important that the witness sees the judge when this is explained.

Care should also be taken not to put the camera on “over view” at any stage if there are issues with the witness seeing the accused or other persons present in the court.